Is Dimethyl sulfide really a sign of foreign life?

Dimethyl sulfide is in the news when NASA’s James Web Space Telescope may have detected its relatively high level in an exoplanette environment called K2-18B.

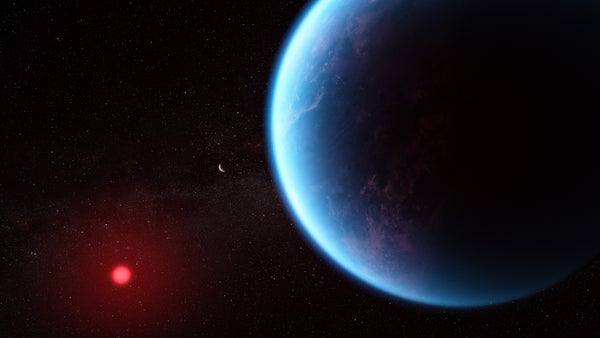

Explanation of an artist of exoplanet K2-18B.

NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmusted (STSCI)

After studying the atmosphere of an exoplanet called K2-18 B with James Web Space Telescope of NASA, scientists and supernatural enthusiasts have announced that they only detected a high level of chemical dimethyl sulfide or made them burn as a uniform life as a uniform compound. Although most people have never heard of dimethyl sulfide, it is around us on Earth. But what is this compound, and is it really a sign of life beyond Earth?

What is dimethyl sulfide?

In chemical terms, dimethyl sulfide has an atom of sulfur tied to two methyl groups, each of which has one carbon atom and three hydrogen atoms. The result is a small molecule in which the human nose has an external capacity for the nose. Elonore Brown, a chemist at the University of Colorado Boulder, says, “None of these sulfur things are going to be a super stinky – garlic, smell of rotten eggs.”

On supporting science journalism

If you are enjoying this article, consider supporting our award winning journalism Subscribe By purchasing a membership, you are helping to ensure the future of impressive stories about discoveries and ideas that shape our world.

Earth’s domethyl sulfide is constantly being produced by small plankkas in the oceans. From there, it grows in the atmosphere, where it makes about one of every Arab molecules. Once each individual molecule of aloft, dimethyl sulfide lasts only for hours or, most, about a day before it is destroyed in reactions that occur due to exposure to sunlight and various atmospheric compounds.

This process is scientifically important on the surface, says brown, as those reactions eventually produce small particles called aerosols that make seed clouds, dimetheyl sulfide a significant compound to understand for climate models and other atmospheric sciences.

From Earth to K2-18 B

Because germs produce all detectable dimethyl sulfide in the Earth’s atmosphere, and because it breaks so quickly, scientists have long held that the compound can be a so-called bioscnecular-a fingerprint of life that is detected by a distance-on our other planets. “On Earth, it is actually considered a clean, vague bioscnecular,” says Nora Honey, a chemist at Burn University in Switzerland.

Enter JWST, a piece of technology with an unprecedented ability to smell atmospheric chemicals on planets passing between your stars and binoculars. Scientists arranged to study the K2–18B for JWST, which in 2015 was discovered to revolve around the Earth to revolve around the 124 light-year. The size of the exoplanet appears between the Earth and the Neptune and belongs to a limit that scientists have never seen closed.

Researchers led by researchers led by Nikku Madhusudan of Astro Physics at Cambridge University in 2023, Announced the first signs of dimethyl sulfide In the atmosphere of K2-18 B. At that time, other scientists were unable to detect. But on Wednesday, Madhusudhan and his team announced that another JWST tool had detected either compound or uniform potential bioscnecular, dimethyl dysalfide, which is more than confidence than previous comments and is higher than the Earth’s atmosphere. New results were published on 17 April Astronomy,

During a presentation aired on YouTube on 17 April, he said, “You need thousands of times of Earth concentrations to be able to explain the data.”

To take “bio” out of bioscnecher?

The new JWST comments-and calculated that the K2–18 B is located at some distance from its star, allowing liquid water to be on its surface-Madhusudan concluded that the most logical explanation is that the planet is covered in a ocean of hot water, which is “with life”.

But both Hanny and Brown did recent research, showing that it would be a stretch to rely on dimethyl sulfide as a decisive sign of life. Brown and his colleagues Produced it and similar compounds in the laboratory simulation of the Earth’s early atmosphere– Including living organisms. Hanny and her team 67p/churyumov-gerasimenko a molecule detected on a frozen comet calledWhich was discovered closely by the European Space Agency with its Rosetta Mission.

Both researchers emphasize that scientists do not know enough about the K2–18 B to determine whether any demethel sulfide found in its environment was produced by living organisms-or by a inorganic event that led to their own observation. Researchers do not even know that the compound will disappear rapidly as it does in the Earth’s nitrogen-rich environment, given that the atmosphere of the foreign world dominates instead of carbon dioxide.

“Chemistry and the planets and all those processes are very diverse,” brown says. “Always there is going to be a way to make something.”

And if life is producing dimethyl sulfide, then the same life should produce other compounds, says Chris Lintot, an astronomer at the University of Oxford. “(Dimethyl sulfide) must be present in a chemical network. If it is produced by biology, it should break, and raw materials – such as H.2S (hydrogen sulfide) – It should also appear in the spectrum to make it. They are not. ,

Overall, they argue that the local reference will always determine what some bioscnechers make. He says, “What is biological on earth, it is not a good guide that can be biological elsewhere.”