Marginal place

Marginal placeStec, mashed potatoes and desserts for astronauts may soon be grown from individual cells in space if an experiment launched in orbit is successful today.

A European Space Agency (ESA) project is assessing the so-called laboratory-developed food in low gravity and in high radiation in the classroom and in high radiation on the world.

ESA is financing research to detect new ways to reduce the cost of feeding an astronaut, which can cost up to £ 20,000 per day.

The team involved states that the experiment is a first step to develop a small pilot food production plant at the international space station at two years.

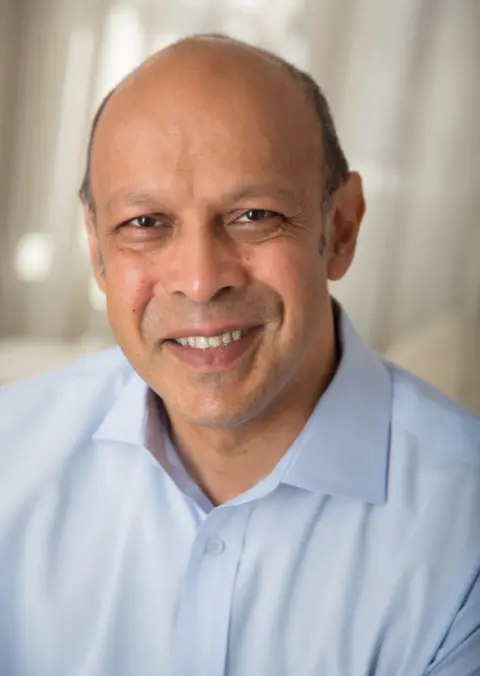

If NASA’s humanity had the purpose of feeling a multi-concert species, then lab-Gro food would be necessary, Dr. The founder of Akil Shamsul, the CEO and the founder of the Bedford-based Frontier Space, who is developing the concept with researchers from Imperial College, London, claims.

“Our dream is in the classroom and the factories on the moon,” he told BBC News.

“We need to build manufacturing facilities from the world, if we provide infrastructure to enable humans to stay in space and work”.

NASA

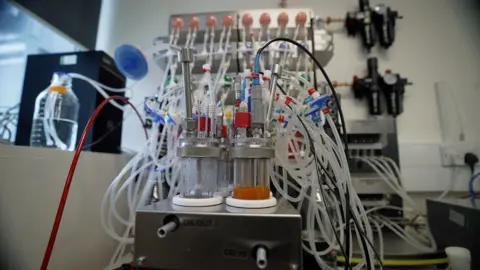

NASALab-Gro food includes test tubes and vats to increase foods such as protein, fat and carbohydrates and then process them to look and taste like normal food.

Lab-Gro Chicken is already on sale in the US and Singapore and is waiting for the approval of Lab Grow Stek in the UK and Israel. On Earth, environmental benefits are claimed for technology on traditional agricultural food production methods, such as low land use and greenhouse gas emissions are reduced. But the primary driver in space is to reduce the cost.

Researchers are experimenting as it costs a lot to send astronaut food on ISS – up to £ 20,000 per astronaut per day, they guess.

NASA, other space agencies and private sector firms plan is a long -term appearance on the moon, orbiting space stations and perhaps one day on Mars. This would mean sending food for tens and eventually hundreds of astronauts will have to work in hundreds of space living and working in space – something that will be prohibited when sent by rocket, Dr. Dr. According to Shamsul.

Growing food in space will make more understanding, he suggests.

“We can only start with more complex foods with protein-dreamed mashed potatoes that we can put together in space,” he tells me.

“But in the long period we can put the lab-Gro content in a 3D printer and whatever you want you print at the space station, such as Stake!”

It looks like replication machines on the star trek, which are capable of producing food and drinks from pure energy. Dr. Shamsul says, but it is no longer the item of science fiction.

He showed me a set-up, which is called a biorite in the Bezos Center for Sustainable Protein of Imperial College in West London. It included a brick-ring coniferous bubbling in a test tube. This process is known as an accurate fermentation, like the fermentation used to make beer, but isolated: “precision” is a rebranding term for genetically engineers.

In this case, Director of Bezos Center, Dr. According to Rodrigo Ladesma-Amaro, a gene has been added to the yeast to produce additional vitamins, but in this way all types of ingredients can be produced.

“We can make all the elements to cook food,” Dr. Ladesma-Amaro says proudly.

“We can make protein, fats, carbohydrates, fiber and they can be added to make separate dishes.”

A very small, simple version of the biorector has been sent into space on a spacex Falcon 9 rocket as part of the ESA mission. There is a lot of evidence that foods can be successfully grown from cells on Earth, but can this process be repeated in weightlessness and high radiation of space?

The DRS Ladesma-Amaro and Shamsul have sent small amounts of yeast to the Europe’s first commercial withdrawal spacecraft, a small cube satellite on Phoenix, to revolve around the Earth. If all go to plan, it will revolve around the Earth for about three hours before falling back from the coast of Portugal to Earth. The experiment will be recovered by a recovery vessel and sent back to the laboratory in London.

Dr. According to Ladesma-Amaro, the data they collect will inform the creation of a large, better biorite that scientists will send to space next year.

However, the problem is that the brick-colored Go, which is dried in a powder, looks uniquely unexpected-even less delicious than the freeze-dry fare that astronauts have to be placed in the present.

This is where the master chefs of the Imperial College come. Jakub Redzicovsky is a Pakistani education designer who converts chemistry into dishes.

Kevin Church

Kevin ChurchThey are yet to use lab developed materials to make dishes for people, as regulator approval is still pending. But he is starting a head. For now, instead of laboratory-developed ingredients, Jakub is using starch and protein from fungus being naturally occurring to develop its dishes. He tells me that all types of dishes will be possible, once he proceeds to use laboratory-developed materials.

“We want to make food that is familiar with astronauts that are from different parts of the world so that it can provide comfort.

“We can make anything from French, Chinese, Indian. It will be possible to repeat any kind of dishes in space.”

Today, Jakub is trying a new recipe of spicy dumplings and needle sauce. He tells me that I am allowed to try them, but the Taster-in-Chief is more worthy of: UK’s first astronaut Helen Sharman, who also has a PhD in Chemistry.

Kevin Church/BBC News

Kevin Church/BBC NewsWe tasted steaming dumplings together.

My idea: “They are absolutely grand!”

Dr. Sharman’s expert view, not disagreement: “You get a really strong explosion from taste. It is really delicious and too much,” she smiled.

“I would like something like this. When I was in space, I had a really long life: tins, freeze dried packets, stuff tube. It was fine, but not tasty.”

Dr. Sharman’s more important observation was about science. Lab-Gro food, he said, may potentially be better for astronauts, as well as reduce the cost to the levels required to make the long-term off-world habitat viable.

Research on ISS has shown that the bio chemical of astronauts changes during long -term space missions: their hormone balance and iron levels change, and they lose calcium from their bones. Dr. Sharman says that astronauts take supplements to compensate, but lab-Gro food can be held in theory with additional ingredients already created.

“Astronauts lose weight because they are not eating so much because they have no variety and interest in their diet,” he told me.

“So, the astronaut may be more open to something that is cooked with scratches and a feeling that you are actually eating nutritious food.”

Get our major newspaper with all the headlines that you need to start the day. Sign up here.