Climate and Science Reporter

BBC/Kevin Church

BBC/Kevin ChurchA world famous tourist industry located at the top of the sheer rocks of Santorini is worth millions. The risk of an omnipotent explosion below is the risk risk.

A huge ancient explosion created a Swapnil Greek island, causing a huge pit and a horse-shine-shaped rim.

Now scientists are investigating for the first time how dangerous the next big can be.

BBC News spent one day in the British Royal Research Ship The Discovery, as they discovered clues.

BBC/Kevin Church

BBC/Kevin ChurchA few weeks ago, about half of the 11,000 inhabitants from Santorini fled for safety when the island closed in a series of earthquakes.

It was a rigorous reminder that girrose restaurants, warm tubs in AirBnB, and vineyard vineyard barriers on rich volcanic soil, grind into the earth’s crust under delightful white villages with two tectonic plates.

Prof., Expert on a highly dangerous submarine volcano with the UK National Oceanography Center, Isobel Yeho has led the mission. About two-thirds of the world’s volcanoes are under water, but they are hardly monitored.

“It is’ like vision, out of mind” in terms of understanding their danger than more famous people like Vesuvius, “she says on deck, as we see two engineers winning a robot, which is the size of the car from the shore of the ship.

This work, coming immediately after the earthquake, will help scientists to understand what type of seismic disturbance can indicate from a volcanic explosion that it is adjacent.

Isobel says that the last explosion of Santorini was in 1950, but recently there was a “period of disturbance” in 2012. Magma was swept away in volcanoes chambers and “swollen” into the islands.

BBC/Kevin Church

BBC/Kevin Church“Underwater volcanoes are actually capable of large, really destructive explosions,” she says.

She says, “If you are used to act safely with small explosions and volcanoes, we are involved in a sense of false security. You believe that the next will be the same – but it may not happen,” she says.

The Hung Tunga explosion in Pacific in 2022 produced the largest ever underwater explosion, and created a tsunami in the Atlantic, a tsunami with shockwaves felt in the UK. Some islands in Tonga near the volcano were so devastated that their people never returned.

Under our feet on the ship, 300 meters (984 ft) below, hot vent bubbling. These cracks in the Earth change the sea shore in the bright orange world of sea rocks and gas clouds.

“We know more about the surface of some planets, what is there,” Isobel says.

The robot descends into the seabed to collect fluids, gases and snap with a piece of rock.

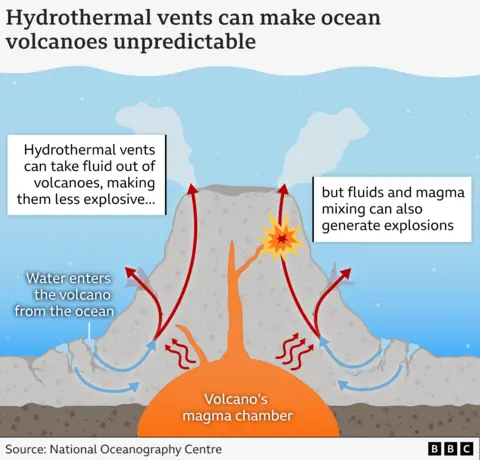

They are vent hydrothermal, meaning that hot water comes out of cracks, and they often make near the volcano.

They are that Isobel and 22 scientists around the world are on this ship for a month.

So far, no one has been able to do any work if a volcano becomes more or less explosive when the sea water is mixed with magma in these vents.

“We are trying to map the hydrothermal system,” Isobel explains. It is not like making a map on the ground. “We have to look inside the earth,” she says.

The discovery is investigating the Caldera of Santorini and sailing for other major volcanoes, Colombo in the region, about 7 km (4.3 mi) in the north-east of the island.

Two volcanoes are not expected to burst adjacently, but it is only a matter of time.

The campaign will create data sets and Geohazard maps for Greece’s Civil Protection Agency, which describes Prof. ParaskV Nomico, a member of the government emergency group daily during the earthquake crisis.

He is from Santorini, and grew up hearing his grandfather about the previous earthquakes and explosions. The volcano inspired him to become geologists.

“This research is very important because it will inform the locals how active the volcano is, and it will map the area that will be forbidden to reach during the explosion,” she says.

She states which parts of the Centorini C floor are the most dangerous, she says.

These missions are incredibly expensive, so isobels are in the form of crams in night and day experiments as scientists work in 12-hours shifts.

John Jaimison, a professor at the Memorial University in Canada in Newfoundland, shows us the volcanic rocks extracted from vents.

“Don’t pick up that one,” he warns. “It is full of arsenic.”

Pointing to each other that looks like a black and orange merging with gold dust, he explains: “This is a real secret – we don’t even know what it is.”

These rocks explain the history of fluid, temperature and material inside the volcano. “This is a geological environment that is different for other people – it is really exciting,” they say.

But the beating of the mission is a dark shipping container on the heart deck where four people stare at the screen on a wall.

Using a joystick that will not look out of a place on a gaming console, two engineers run underwater robots. Isobel and ParaskV trad the principles about the robot found in a pool of fluid.

They have recorded very small earthquakes around the volcano, which is moving through the system due to the fluid and causes fractures. Isobel has played us the role of an audio recording of fracture. It seems that the bass is being up and down in a nightclub.

They recognize how fluid moves through rocks by pulsing an electromagnetic field in the Earth.

This is making a 3D map that shows how the hydrothmal system is connected to the Magma Chamber of the volcano where an explosion occurs.

ParaskV says, “We are doing science for people, not science for scientists. We are here to make people feel safe.”

The recent earthquake crisis in Santorini highlighted that the inhabitants of the island have been told about the seismic threats and how many dependent they are on tourism.

Back to dry land, photographer Eva Randal meets me at my favorite place for wedding shoots. When the so -called herd of earthquake in February, he left the island with his daughter.

BBC/Kevin Church

BBC/Kevin Church“It was really scary, because it became more and more intense,” she says.

She is now back but the business is slow. “People have canceled the booking. Generally I start shooting in April, but my first job is not May,” says Eva.

In the main category of the upmarket town Oia of Centorini, British-Canadian tourist Janet told us that six of their 10 groups canceled their holiday.

She believes that more accurate scientific information about the possibility of earthquakes and volcanoes will help others feel more confident about traveling.

“I get Google Alert, I get alerts from scientists, and it helps me feel safe,” he said.

BBC/Kevin Church

BBC/Kevin ChurchBut Santorini will always be a dream destination. In Imerovigli, we see two people climbing on curved roofs to get the right shot.

Couple – Married for just 15 minutes – traveled from Latvia and not poured from the risks under the island.

“In fact we wanted to marry a volcano,” Tom says, her bride Christina from her side.

Additional Reporting by Tom Ingam and Kevin Church, Climate and Science Team