There are many changed parts in the human body today, including artificial heart to myolectric feet. It is possible that there are not only complex techniques and delicate surgical processes. This is also an idea – that humans can change the body of patients in the highest difficult and aggressive way.

Where did that idea come from?

Scholars often depict American Civil War as an initial watershed for dissection techniques and prostheses design. The disintegration was the most common operation of the war, and in response an entire prosthetics industry developed. Anyone who has watched a civil war film or TV show has probably seen at least one scene of a surgeon who has reached the injured soldier with Ara in his hand. The surgeons spent 60,000 dissection during the war, spent for three minutes per organ.

Nevertheless, a significant change in practices around the disadvantage of the organ began long ago – in the 16th and 17th century Europe.

As a historian of early modern medicine, I find out that the western approach towards surgical and artisan intervention in the body began to change about 500 years ago. Europeans went to the 1500 to disintegration for the prosthesis of the organs and to hesitate for some options, for many dissection methods and complex iron for a full of 1700.

The dissection due to the high risk of death was seen as the last remedy. But some Europeans started believing that they could use it with prostheses to shape the body. This break from a millennium-lambi tradition of non-conscious treatment still affects the modern biomedicin by giving ideas to the doctors that it is a good thing to change it significantly and embedd the technology to cross the physical boundaries of the patient’s body. Can A modern hip replacement would be unimaginable without that underlying perception.

Surgeon, gunpowder and printing press

The early modern surgeons argued with passion to where and how to cut the body to remove fingers, toes, hands and feet from the methods of medieval surgeons. This was partly because he faced two new developments in the Renaissance: the proliferation of gunpowder warfare and printing press.

Surgery was a craft that was learned through the training and in the years of traveling to train under various masters. Exercises of topical ointments and minor processes such as settled bones, bringing boils and day-to-day practice of sewing surgeons. Due to their danger, major operations such as dissection or trepanations – a hole drilling in the skull – were rare.

The widespread use of firearms and artillery separated traditional surgical practices in ways that required immediate dissection. These weapons made tissue crushing, interrupting blood flow and introducing debris – from wooden splashes and metal pieces to clothing scraps – deep infections and gangrene in the body made infections and gangrene to infection and gangrene. Mangald and Gangris organs forced surgeons to choose from aggressive surgery or let their patients die.

The printing press, while struggling with these injuries, gave the means to spread their thoughts and techniques beyond the battlefield. The processes described by them can be fierce in their texts, especially because they operate without anesthetics, antibiotics, infections, or standardized sterilization techniques.

But each method had an inherent justification. Strike with one hand with a malelet and chisel caused dissection quickly. Patients were prevented from bleeding, cutting through disencisted, dead meat and burning the remaining dead substance with a cater iron.

While some more and more healthy wanted to save the body, others stressed that it was more important to shape the organs so that patients could use prostheses. European surgeons had never advocated dissection methods based on placements and use of prostheses before before. Those who used to do this were coming to see the body, because the surgeon should only preserve this, but should mold the surgeon as a surgeon.

Amputees, artisans and prostheses

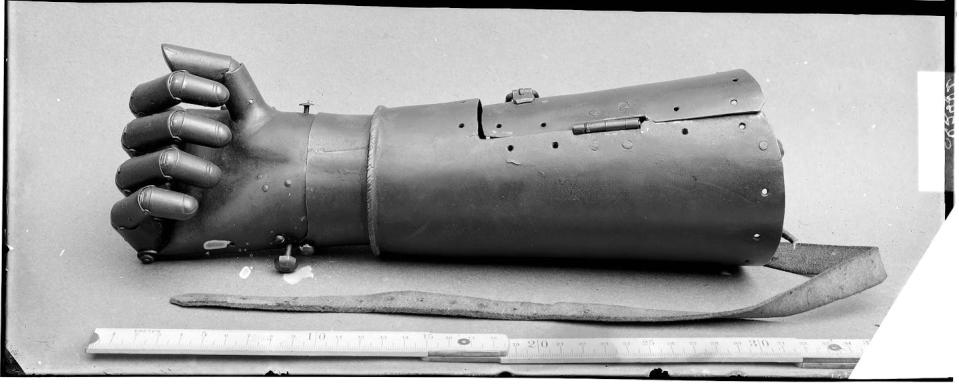

As the surgeon detected surgical intervention with saws, the Emputes used with artificial limbs. Wooden peg equipment, as they had been for centuries, remained a normal lower limb arts. But creative collaboration with the artisans was the inspiring power behind a new artificial technology that began to appear at the end of the 15th century: Mechanical Iron Hand.

Most of the experiences from written sources are rarely revealed that survived the organ dissection. The survival rate can be reduced by up to 25%. But in those who made it, artifacts show that it was important to work how they navigated their environment.

This reflected a world in which prosthetics were not yet “medical”. Today in the US, a doctor’s recipe is necessary for an artificial limb. Early modern surgeons sometimes offered small equipment such as artificial nose, but they did not design, make or fit prosthetic organs. In addition, there was no business compared to today’s prosthetists, or health care professionals, who form prostheses and fit. Instead, early modern amputees have used their own resources and simplicity.

Iron’s hands were improved. Their movable fingers were closed in different positions through the internal spring system. They had a lifetime details: engraved nails, wrinkles and even meat-tond paint.

The wearers operated by pressing them down on the fingers to lock them in position and activate them on the wrist. Some of the iron hands run together, while in others they move individually. The most sophisticated is flexible in every joint of every finger.

The complex movement was more to influence supervisors than practicality everyday. Iron hand was the Renaissance precursor for today’s prosthetics industry’s “Bonic-Hand Arms Race”. The more attractive and high-technical artificial hands-now and now are less inexpensive and user friendly.

The technique was attracted to stunning places including locks, watches and luxury handguns. In a world without today’s standardized model, the initial modern Emputies fined the artificial limbs with scratches by entering the craft market. Between an Empty and an Gennavan Clockmaker as a 16th -century contract, buyers dropped into artisans shops, who never created an artificial limb to see what they could do.

Because these materials were often expensive, the wearer was rich. In fact, the introduction of iron hands marks the first time period when European scholars can easily distinguish between different social classes based on their prostheses.

Powerful idea

The iron hands were important carriers of ideas. He motivated the surgeons to think about prosthesis placements when he operated and created optimism what humans could achieve with prostheses.

But scholars have recalled how and why iron hands made this effect on medical culture because they have been fixed too much on a kind of wearer – knights. Injured knights offer traditional assumptions that use iron hands to keep their horses reins, only offer a narrow view to survive living artifacts.

A famous example colors this interpretation: the “second hand” of the 16th -century German Night Gotz von Berlichingan. In 1773, the playwright Goethe attracted a dramatic and a play with a drama about a charismatic and fearless knight, which “freedom – freedom – freedom! (Historical Gotz died of old age.)

The story of Gotz has since inspired the philosophy of a bionic warrior. Whether in the 18th century or in the 21st, you can find mythological depiction of Gotz standing in front of the authority and hold the sword in your iron hand – an impractical achievement for their historical prosthesis. Till some time ago, scholars believed that all iron hands were of knights like Gotz.

But my research shows that many iron hands show no signs of having warriors, or perhaps even for men. Cultural pioneers, many of whom are known only from artifacts they had left behind, attracted on stylish trends that procure clever mechanical equipment, such as the short clock genine of the short watch displayed in the British Museum today. In a society that distinguished the simple objects that staining the boundaries between art and nature, the Emputes used iron hands to defy negative stereotypes, which reflect them as pathetic. The surgeon noted these devices, praising him in his treaty. Iron hands understood a physical language contemporaries.

Before the modern body of changed parts may be present, the body should be rebuilt because some humans may adapt. But this remagins required more efforts than surgeons only. It also supported amputees and artisans who helped in the creation of their new organs.

This article has been reinforced from the interaction, a non -profit, independent news organization, which brings you facts and reliable analysis to help you understand our complex world. It was written by: Heidi Haus, Oborn University

Read more:

Heidi House received funds from Herzog August BiblioCo in 2012, Consortium for Science, Technology and Medical History in 2014-2015, American Council of Seeking Society in 2015-2016, Huntington Library and Society of Society 2016- Scholars in Humanities at Columbia University in 2018.