Technology reporter

Mater

MaterFor a country famous as the European address of Big Tech, Ireland’s hospitals are often far behind in technology.

When they walk between the clinics, people have a lack of shared computerized patients, or unique identifiers to track people.

In July 2024, the failure of a computer system returned the surgery to Dublin’s Mater Hospital and asked people not to come to its A&E.

Three years ago, the Russian ransomware attackers shut down the entire computer network of the Irish health system, and published a medical record of 520 people online.

But Ireland now has ambitious goals to modernize their healthcare.

He is also involved A program called sláintecareDecreed in 2017, the plan is to create a healthcare service to use some of its € 22.9BN (£ 20bn; $ 24bn) budget surplus which is free at the point of care like UK or Canada.

To improve healthcare, pinch points such as diagnostics have to be improved.

This is the problem of dealing with 164 years old at Metter Hospital in Dublin and the location of Ireland’s busiest emergency department.

This is especially in winter, when there were 444 people on trolleys in the Irish A&E departments in early January, waiting to see.

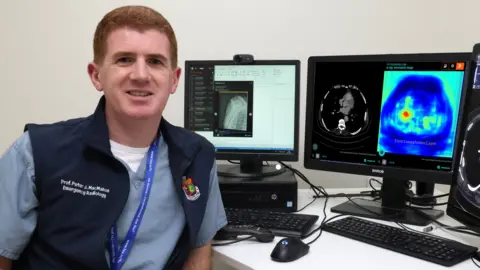

Radiologist Prof. Peter McMahon, a advisor to Mater, says, “In Ireland, the major problem we have is, and especially in waiting for diagnostics, for MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) or CT (computed tomography) scan,”.

Due to Professor McMahon, who was dubbed as a hobbist programmer as a medical student, Matter is now one of the first hospitals in Ireland, which is to use artificial intelligence (AI) in its radiology department – a hospital share that provides medical imaging to diagnose diseases and guide treatment.

To ensure that patients with the most essential needs are seen first, Prof. McMahon says: “We use AI, which analyzes all head scans for bleeds, all chest scans for blood clots and all bone X-rays for fractures.”

AI is particularly helpful in assisting young doctors, when they do not have to turn experienced advisors.

“Now on 2am a nurse or junior doctor is not alone, he got a wing man,” he says.

Mater Hospital

Mater HospitalRural hospitals face different types of challenges.

The University Hospital in Dongal is without MRI facilities in the evening and weekend.

Currently, a patient of MRI scan at night may face an ambulance ride for Dublin.

But now, Prof. McMahon and AI Research Fellow Paul Banhan of McMahon and Matter trained a test AI model to create “synthetic MRI” from CT scan, to immediately try patients with suspected spinal injuries.

It was done on the same person by feeding about 9,500 pairs of 9,500 pairs “generative AI” models of the same region’s CT and MRI images.

Now AI can predict what the MRI scan will look from CT scan, some available in all emergency departments.

And since radiology scans also come with doctors’ text reports, he is also searching using a large language model to identify important disease patterns and trends.

Peter McMahon

Peter McMahonIt is easy to implement AI for medical images in Ireland as the country has stored a scan in a central, digital filing system since 2008.

But many other important information, such as medical notes or electrocardiogram (ECG), in most Irish hospitals or in small databases, remains largely in paper format which are not shared centrally.

Professor McMahon explains that there will be “seriously delayed” in implementing AI to spot potential diseases and improve clinical care.

The aging IT system in Irish Healthcare is more widely a challenge.

Dr., a senior computer science lecturer of Technological University Dublin, Dr. Robert Ross says, “quite clearly, a lot of hospitals are working with heritage IT system, where they are just trying to keep the show on the road.”

“It is not easy to do anything else to integrate AI,” they say.

Using AI in healthcare is not without problems.

An example here is the AI speech-recognition tool. By using them, doctors can be allowed to take notes and spend less time on report writing.

But some are found To make thingsNon-existent medication involves invention.

To prevent such AI from hallucinations, “You need to ensure that it is punished in its training, if it gives you something that does not exist,” says Prof. McMahon.

AIS may have prejudice, but “humans also have prejudice”, he explains.

A tired doctor expects a young patient to be healthy, ignoring their blood clots.

“For whatever reason we are more open to accept human error”, where “acceptable risk is zero”, a advisor to Talghat University Hospital and Professor Pro Scene Kanelli at Trinity College Dublin.

This means that we “continue with the illusion of 100% accuracy in humans”, and ignore areas where AI-supported technology can make better clinical decisions, they say.

Talghat University Hospital

Talghat University HospitalHealthcare regulators, who already have the “weak enough” understanding of the software as a medical tool, have not caught at all with the rules for AI, Dr. Aden Boron, the founder of an Irish medical tech start-up, Dr. Aidan Gite Labs, and a researcher from Dublin City University, says.

For example, obtaining a CE mark, which shows that a medical device meets the safety rules of the European Union, providing details about the factory where the product has been manufactured.

But in the case of software which is not relevant, Dr. Boron says. “For us, manufacturing literally means mimicking software,” he explains.

AI can have a black box problem: We can see what goes and what comes out in them, but the deep learning system powering these models is so complex that even their creators do not understand what happens inside them.

This can create difficulties for a doctor, who is trying to explain the decisions of treatment to include AI, Dr. Paul Giligan, Head of Mental Health Services of St. Patrick, Dr. Paul Giligan says, one of the largest mental health providers in Ireland who runs a St. Patrick Hospital in Dublin.

When AI affects their decisions, doctors “need to be able to clarify the logic behind the decisions that are accessible and understandable to the affected people,” they say.